Prof. Arthur LaBrew, Musicologist

B

Bethel, Thomas (1868-)

Musician in a hotel. Born Virginia, age 42, married 6 years. Toured England.

[Census NYC 1910 ED 1283/10B.]

Bethune, Thomas Greene aka Blind Tom (1849-1908)

Bethune, Thomas Greene aka Blind Tom (1849-1908)

The most important Blind pianist of his century. Born near Columbus, Georgia, the son of Mingo and Charity Bethune, slaves of General James N. Bethune. There are many accounts of the early beginnings of Tom’s career and his ability to perform difficult music after one hearing.[1] The conflicting statements contain many variances and thus the following, taken from the court proceedings against General Bethune, are used for this biographical statement. Tom, with two sisters and his father and mother, were to be sold at a public auction but at the request of the parents, the whole family was purchased. Tom was blind at this time (1850) and about 8 months old. He showed no signs of emotional imbalance until his fourth or fifth year. He soon discovered the piano and General Bethune gave him free access to the instrument. He began to play everything he heard and when about six years old was sought out for exhibition purposes at Savannah, Georgia. He was subsequently hired to one Mr. Oliver who traveled with him over the country for five or six months.[2]

After the war was over, Tom was brought to Northern cities for exhibition. While in Cincinnati, Ohio, one Tabb Gross, the “Barnum of the African race,” sued General Bethune, alleging that Tom was being mistreated and that the General had reneged on a promise to buy an interest in Tom. The court sided with General Bethune on grounds that Tom was old enough to make his own decision and was no longer a slave. It appears that Tom, under questioning by the Judges, made it clear that he wanted to remain with Bethune, someone he knew, rather than go with a stranger.

After the war was over, Tom was brought to Northern cities for exhibition. While in Cincinnati, Ohio, one Tabb Gross, the “Barnum of the African race,” sued General Bethune, alleging that Tom was being mistreated and that the General had reneged on a promise to buy an interest in Tom. The court sided with General Bethune on grounds that Tom was old enough to make his own decision and was no longer a slave. It appears that Tom, under questioning by the Judges, made it clear that he wanted to remain with Bethune, someone he knew, rather than go with a stranger.

The New York Times, reporting the case, accused the General of “self-interest; that now since the war was over, he would try to accumulate some of those ‘Yankee dollars’.” During this period, Tom was still being exhibited in Cincinnati, the publicity of the trial being reported in the press, and after a brief tour of the free states, he was taken overseas where various persons testified to his ability to repeat difficult music.[3]

The fact that Tom was lacking in “reason and judgment” did not detract from the fact that he had genius, if only that of being a mechanical imitator. During the course of his tours, it is frequently mentioned that teachers in the “science of music” might do well to study this phenomenon to see how he managed execution while not knowing the different methods of the period. Various tests were given him by audiences to try his memory which led to his accumulation of nearly 7,000 pieces(!). The musical material ranged from Beethoven’s Sonata Pathetique to Mendelssohn’s Concerto in G minor. At the same time, he mastered such solos as the Thalberg Fantasias and works by Liszt, Hoffman, Chopin, Heller, and others.

Tom was finally freed in a court case in 1884 (see Free At Last, 1876).[4] The New York Times mentioned 4 concerts he gave in Septemeber, 1887 the first since he obtained his freedom.[5]

In or near 1890, another court case removed him from General Bethune to the custody of his daughter-in-law, Elsie, who resided in Hoboken, New Jersey. Mrs. Bethune came under court scrutiny in 1894 for not paying the sum of $3,304 to the administratrix of the estate of lawyer Daniel D. Holland for legal services (1884). It was brought out that Mrs. Bethune had earned $33,000 since she had custody of Tom.[6] In spite of such controversy, she must have taken care of him well during the period 1890-1908. In a “Guessing Contest” sponsored by the Indianapolis Freeman (1890) seeking the public’s awareness of the “Ten Greatest Negroes,” surprisingly Tom’s name appeared 8 times among a host of VIP names! He still makes tours and is dead by June 13, 1908.

In 1895 his sister, Dollie Tyson, died at her home in Columbus, Georgia, age 70 years and his mother in 1904.[7]

In 1912, the will of Elise Bethune Lerche was contested being a disposal of $70,000 in Perogative Court on the grounds that she lacked testamentary capacity.[8]

The most important thing that could be said of Tom is that he was by far superior in actual playing than most of the second-rate pianists and comparable to many a so-called first rate artist. His playing contained such desired results as accuracy and did (according to newspaper sources, in spite of the opinions of many impartial musicians) contain individual expression, showing that he was able to do musically what some had to be taught.

His musical output, if one takes time to examine the record clearly, merely shows how he was exploited. Some of the pieces contain passages of great clarity, while others are not so well put together. Tom, of course, did not write down his own music, but as was frequently done in that period, the notes were copied from his performances. His appearance in New Orleans in 1860 certainly sparked Adolph Périer to attempt to exploit the young black pianist, Basile Barès.* In 1867 there was a second attempt at exploitation when Blind Sam* was introduced to the public performing a repertoire similar to Blind Tom. Of course, neither Barès nor Blind Sam ever achieved the great publicity of the original. In 1868 A. J. Goodrich published his La Pacifique, valse de Salon (Ditson, 1868, Plate 24643), ded. a Monsieur Joseph Heine. An added note read “As performed with great applause at the Concerts of Thomas Green Bethune (Blind Tom).” Copy at Michigan Music Research Center, Inc. Less explored in the Blind Tom biography.

are his feelings about his music performances thus presuming that even in his idiotic state he had none! Portrayals of his life should not omit relative comment.

The Marsh & Bubna Catalogue (back cover of The Guard’s Waltz by D. Godfrey) gives the following compositions by Blind Tom:

Songs: Mother, dear Mother, I still think of Thee (30)

Waltzes & Gallops:

Basso Tuba Waltz

Blind Tom Waltz

Vivo Gallop

Marches, Quicksteps, &c.

Blind Tom’s March

Columbus March

Gen. Howard’s Grand March

Blind Tom Mazurka (Beckel, played by Tom, 1865 Philadelphia J. Marsh)

Rondos, Variations, &c.

Cruel War is over, Variations

Rain Storm

Blind Tom’s Compositions

Basso Tuba Waltz

Blind Tom’s March

Blind Tom’s Waltz

Blind Tom’s Mazurka

Blind Tom’s Polka

Blind Tom’s Schottisch

Columbus March

Cruel War, Fantasie

Gen. Howard’s March

Rain Storm

Vivo Gallop

Works already re-discovered (including republished versions)

1860 Virginia Polka (NY H. Waters]; Michigan Music

Research Center, Inc.

1860 Oliver Gallop (NY H. Waters)

1864 Academy Schottische (W. P. Howard)

Academy Schottische (Ditson, 1888)

Academy Schottische (Thos. G. Bethune, 1892)

1865 Blind Tom’s Waltz (J. Marsh, Phil.)

Blind Tom’s Waltz (Ditson, 1888)

Blind Tom’s Waltz (T. G. Bethune, 1892)

1865 Blind Tom’s Mazurka (J. Marsh, Phil.) by J. C. Beckel; rev. L. K. 1888

1865 General Howard’s March (J. Marsh, Phil.); Michigan Research Center, Inc.

1865 Basso Tuba, waltz (Y. Marsh, Phil.)

1865 Rainstorm (J. Marsh, Phila.) (W. P. Howard)

Rainstorm (Ditson, 1888)

Rainstorm (Ditson, 1892), T. G. Bethune

1865 Vivo Galop, Op. 4 (J. Marsh Phil.) 1029 Chestnut St.)

1865 Columbus March (J. Marsh, Phil.)

Columbus March (Oliver Ditson and Co., 1888 and 1889)

1865 Mother, Dear Mother (J. Marsh, Phil.)

1865 Blind Tom’s March (J. Marsh, Phil.)

1866 Battle of Manassus (Root and Cady); various dates of publication, 1866 (Brainard), 1867, 1894, 1898, 1899, 1913; (S. Brainard’s Son, 1884); see also in Brainards Our War Songs for Piano, 1893)

1866 d. to H. K. Benham, Esq. of Ind., Ind. [9] Daylight (Blind Tom or heirs, 1895); see also in Royal Folio of Music (Musical Almanac 1887, W. F. Shaw, Philadelphia, copyright 1886), p. 34

1866 Water in the Moonlight (Blind Tom); also dated 1894,1895, 1898, 1899 (Root and Cady)

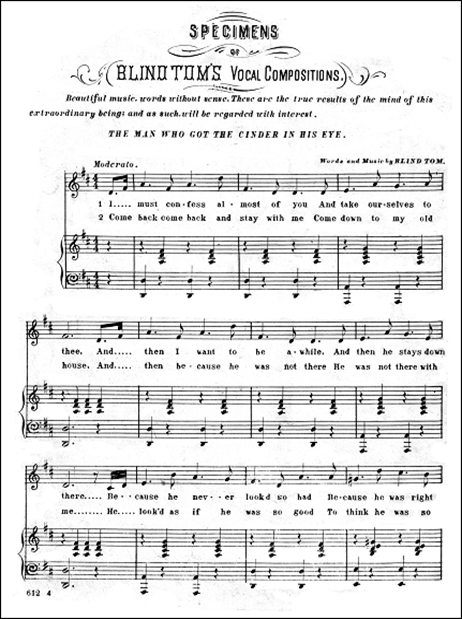

1867 Specimens of Blind Tom’s Vocal Compositions

1. The man who got the cinder in his eye

2. The boy with the axles in his hands

3. The man who snatched the cornet out of his hand

1880 March Timpani (J. G. Bethune); Prof. W. F. Raymond, pseud.

1881 Specimens of Blind Tom’s Vocal Compositions; edition also of 1867

1. Wilt thou bring my baby home

2. The man who mashed his hand

3. Mother wilt thou come and cure me?

4. I wish dear Jodie would come home

5. The man who sprained his knee

1881 Rêve Charmant, nocturne (J. G. Bethune)

1881 Plantation Melodies; 2nd copy dated 1900

1. Waggin’ up Zion’s hill

2. That welcome day

3. Come Along Moses

4. Them golden slippers

1882 Wellenklange (Voices of the Waves) (J. G. Bethune; Francois Sexalise; see also in catalogue of J. H.

Schroeder & Co., NY 1892)

1887 March Lanpier Polka (Frederick Blume; T. G. Bethune)???

1887 Cyclone Galop (Wm. E. Ashnall but later changed to Elise Bethune, 1887 and 1888)

1888 When this cruel war is over (Oliver Ditson and Co.)

1888 Sewing song (J. Schroeder, T. G. Bethune) (W. A. Bpnd)

1888 Concert Hall Polka (Oliver Ditson and Co.)

1899 Military Waltz (Blind Tom; C. T. Messengale, pseud.)

[For a London episode see The Illustrated London News, April 6, 1867, 330 at St. James’s Hall on April 9 and 10 at 3:00 P. M. and again at 8:00 P. M. before proceeding to Paris. W. P. Howard announces himself as the “Musical Guardian of Blind Tom.” Ann Sears article on Blind Tom in Sam Floyd’s International Dictionary of Black Composers, 1999, p. 106ff. is error laden, the music entries incomplete and fails to elucidate his real genius! Article should have been written or corrected by his chief biographer, Dr. Geneva Southall].[10]

Beverly, Minnie (18–)

Of Grand Rapids, Michigan; sings in the Patrick Gilmore program in June, 1890.

Census Grand Rapids, Michigan 1880, 3rd Ward Grand Rapids, ED 140/46B; Plaindealer June 20, 1890; is white wife to John, black (born in Virginia), born in Holland of Holland parents; all of the children are designated “mulatto.”

Census Grand Rapids, Michigan 1880, 3rd Ward Grand Rapids, ED 140/46B; Plaindealer June 20, 1890; is white wife to John, black (born in Virginia), born in Holland of Holland parents; all of the children are designated “mulatto.”

Bias, Charles (1875/6-)

Musician.

Census Washington, D. C. 1910 ED 21 sheet 6b: age 34 born Maryland of Maryland-born parents; in his home are his wife, Mamie (33, born in D. C.) and married 12 years with one living child, Jessie Amno(?), brother (31), Stanley Amno(?), brother (21), Jessie Anderson. brother (31), Lucy Anderson, sister-in-law (33).

Bial=Rabah (600 A.D.-641)

A black poet and musician; reputed to have died in Damascus in A.H. 20 (=641) about age 60 and buried in Dariya; not listed in Encyclopidiae of Islan III.

[Hearn Oriental Studies; Hare, op. cit. 283f.]

Bibb, Henry Walton (1815-1852)

Born in Kentucky, he ran away from his master and located in Canada. Although active there, he frequently was in Detroit in its civic affairs. His sole reason for not remaining in Detroit was due to the possibility that his former-slave master would seek him out and according to the laws of the State would have to be returned if the truth prevailed.

Bibb was frequently called upon as a lecturer and traveled in many places including the Ohio circuit during the 1840s. In 1844 his “Plantation Song” was published[11] purportedly composed by slaves “and when sung properly, possesses a peculiar solemnity of expression, and touches the felling of such as are not seared by the unfeeling influence of Slavery”and reads:

See these poor souls from Africa,’

Transported to America;

We are stolen, and sold to Georgia, will you go along with me?

We are stolen, and sold to Georgia, go sound the jubilee.

See wives and husbands sold apart,

The children’s screams!–it breaks my heart;

There is a better day a coming, will you go along with me?

There is a better day a coming, go sound the jubilee.

Gracious, Lord! when shall it be,

That we poor souls shall all be free?

Lord, break them Slavery powers–will you go along with Me?

Lord, break them Slavery powers, go sound the jubilee.

Dear Lord! dear Lord! when Slavery’ll cease,

Then we poor souls can have our peace;

There is a better day a comning, will you go along with me?

There is a better day a coming, go sound the jubilee.

At these affairs he would sing the old slave or plantation songs. In the 1850s, he decided to publish them and so announced in the press that his Anti-Slavery song book was ready from the press.[12]

His plantation song, also mentioned in the press, was published with a few changes at the Emancipation service of 1846, Bibb, the speaker at the City Hall, and other Blacks sang  “Liberty Songs” and further announced they would exhibit a “Coffal Gang of Slaves” [often spelled “coffle”] who would sing the “Slaves’ Plantation Songs, as usually sung by them when parting to meet no more.”[13]

“Liberty Songs” and further announced they would exhibit a “Coffal Gang of Slaves” [often spelled “coffle”] who would sing the “Slaves’ Plantation Songs, as usually sung by them when parting to meet no more.”[13]

This exhibition has not been noted in the ceremonies on the East coast and, of course, could not have been publicly displayed in southern states.

In addition, Bibb published a newspaper, The Voice of the Fugitive [printed in Detroit] which mentions many affairs of Blacks in the State of Michigan. Much information about the status of the “Underground Railroad” is also given. In his biography he published one of the earliest pictures of the famous “Juba” dance. His description has erroneously been equated to the 1820 period without foundation. Bibb died in 1852 and a suitable memorial was held by the Black citizens aboard the excursion steamer, Ruby.

Works:

The Bereaved Mother

On To Victory (by Rev. Mrs. Martyn)

The Fugitive’s Triumph (parody by Tucker)

Plantation Song (Bibb)

The Bible For The Slave (ded. to Henry Bibb, by Rev. E. . Rogers, of Newark, N. J.)

Set The Captive Free

The Rumseler’s Lament (Bibb)

Biddle, John Henry (1840)

Born in New York; age is 30; in his home are Sarah, 27, Eligin, 9, Ellen A., 3 and John T., 5/12.

Census Philadelphia 1870, Wd. 8, Dist 23, p. 87.

Biemler, Fédéric (1859-)

Born in La Vera Cruz, Mexico, August 19, 1859; resided in Paris, France. Reputed to be a ‘Negro’ composer. In the Calogo de las piezas de musica publicadas por A. Wagner y Levien, 15 Coliseo Viejo, Mexico, his 3 Danzas para piano are listed: 1. El relojito aquel, 2. Chateau-Maguey and 3. La noche aquella.

Works:

Orchestral

American gavotte,

anniversary march

Autour du rat mort, march

Battura Valse, La

Les champs de Courses,

galop

Chasse au lo(a) pin,

mazurka

Capricieuse, valse

Danse de Cynhalcus

Danse Japonceise

Danse Mexicaine

Elisa, mazurka

Fleurs et confetti, mazurka

Gavotte en ré

Gavotte en sol mi

Navancuse

Larines de femme, valse

Malopocuceku, danse russe

Mantilla, valse

Marche religieuse

Marie, mazurka

Marina, fantasie

Menuetto

Menuetto giocose

Mexicaine, mazurka

Nenette, polka

Papillon blue, mazurka

Du Paris, Montmarte,

marche

Polonaise en ré mi

Petito chats noirs, polka

Regement des femmes,

march

Résignation, mazurka

Révélation, valse

Souvenir aux plus belles,

marche

Souvenirs de l’Eden, marche

polka

Souvenirs Mexicaine, valse

Sur le Hamac, mazurka

Piano

Premiere sonatine

Deuxième sonatine

Flaneuse valse [pour] pfte.

& orchestre

Nocturne

Rêvebsem valse

3 Danzas para piano

El relojito

Chateau-Maguey

La noche aquella

Violin

Barcarolle

Canzonetta

Caprice

Impromptu

Romance de Concert

Rêverie

Vocal

Adieu

Lesoir

Serenade

Ave Maria, chant religieuse

El Bromarzo, operetta

Cavalle de Bejucal, chanson Novanaise

Casse de Cafe, valse

chant(e)

Chante ma mandoline,

romance

Juvalah, chant

Bill (1755)

Flute/fife. Ran away from Jeremiah Platt on July 5, 1780; stood about 5’ 6”; “it is supposed he will attempt to get to New York or within the enemy’s lines;” played well on the flute and fife; $500 reward offered.

[Connecticut Courant, July 11, 1780; Hartford, Connecticut; LaBrew BMCP]

Bill (1757)

Violinist/fifer. Ran away from Adam Galt on June 6, 1784; described as a “Negroe” about 27 years old; 5’ 4” or 5”; his feet had been frost bitten and he had lost his toe nails; “he plays on the fiddle and fife, and is more conceited than good at any of them;” reward of $6 raised in second notice to $8.

[Pennsylvania Gazette, June 30, December 1, 1784; Salisbury Township, Lancaster County, Pennsylvania]

Bill (1787)

Violinist. 20 Dollars reward. Ran away on Friday the 12th day of this month, January, 1810 a Negro Man Slave named Bill. He calls himself Bill Pane, belonging to the subscriber, living at Charles county, state of Maryland. The said slave is a good waiter, and can drive a carriage well. He is 23 years of age, 5 feet 9 inches high, small face, handsome lively eyes, is very fond of spirituous liquors, plays on the fiddle . . . The said slave took a fiddle with him, and it is expected that he intends to go to Frederick Town, Maryland. The above reward will be paid for securing the said slave in any public jail, and reasonable expences, if brought to me in Charles County.” Priscilla H. Courts. NOTICE: Was committed to the goal of Washington county, Maryland, on the 21st ult. as a runaway, a negro man, who calls himself WILLIAM PANE, and says he belongs to Mrs. Priscilla Courts, of Charles county, Md.; he appears to be about 23 years old, about 5’ 9” high . . . The owner is requested to come and release him, otherwise he will be sold as the law directs. Matthias Shaffner, Sheriff of Washington County, Maryland.

[Washington Intelligencer, Friday, February 2, 1810; March 23, 1810]

Billie=Will (1738/9)

Violinist of John Tayloe; probably the earliest black musician involved in an important court decision regarding the “black” citizenship; born about 1739, he had apparently lived in South Carolina but was brought to Virginia by the Hon. John Tayloe; very black about 5’ 8”tall; he executed an escape on July 14, 1768 and was thought to attempt to return to South Carolina where he “expected to be free;” in Virginia he worked at the Occoquam foundry as a ship’s carpenter; Billie was obviously re‑captured for a second notice, February, 1769, noted a new escape date as October 10, 1768; Billie may have been transferred from foundry to the Neabsco Ironworks; he was accompanied on his second escape by a mulatto friend, SCIPIO about October 10, 1768; the second advertisement still referred to his ability to play on the violin; six years later, Billy or Will escaped for a third time, March 16, 1774; the three notices sent to the newspapers were signed by Thomas Lawson. Billie comes to notice towards the end of the War period when he was tried and found guilty of treason against the United States by a Virginia court; one of the executors of the Tayloe estate, Mann Page, wrote to Thomas Jefferson, then the governor, protesting the legalilty of the sentence (letter dated May 13, 1781); Jefferson gave Billy a reprieve until the last day of June. Billy had been sentenced at the Court of Oyer, held at the Court House of Prince William County, May 8,1781; six justices presided; it was determined that Billy, on April 2, 1781, “did feloniously and traitorously adhere to the Enemies of the commonwealth and gave them aid and comfort . . . (and) did in company of and (in) conjunction with divers enemies of the commonwealth in an armed vessel . . . wage and levy war . . . etc.; Billy was found guilty and sentenced to be executed on the gallows on May 25 between the hours of 11 and 2; “his head to be severed from his body and stuck up at some public cross road on a pole.” However, two justices, Henry Lee and William Carr, were against the condemnation sentence for in their opinion, a slave “cannot commit treason against the State not being admitted to the Privileges of a Citizen owes the State no Allegiance and that the Act declaring what shall be treason cannot be intended by the legislature to include slaves who have neither lands or other property to forfeit.” In addition, the two justices were not fullly convinced that Billy had voluntarily gone aboard the enemy’s vessels . . . or took up arms. . . or aided or assisted the Enemy “of his own free will.” Since the law had particularly stated that the method of trying slaves charged with treason provided for a “unanimous” decision by all the five judges, Jefferson’s mandatory reprieve was not to grant Billy’s freedom but merely to stay the execution until the general assembly could act. Page, meanwhile, gathered a petition which was presented to the Virginia House of Delegates, June 7, 1781, for Billy’s pardon and two days later it was read to and agreed upon by the House members. The committee for courts of justice recommended that “the indictment and proceedings thereon against the said slave were illegal.” The entire matter was settled by a joint resolution (rather than by a special legislative bill) which freed Billy, June 14, 1781. Billy’s true status as a “slave” appears to have been the only thing that saved him from a certain death. It had been reported that his worth at this time was 27,000 Pounds “current money;” one wonders, however, if his worth was as a servant or as a prisoner? Or how much was due to his abilities especially as a musician. (It would be most interesting to find what happened to Billy after this episode ‑ did he try other escapes or did he finally settle down to a normal life?). This is a historically important case, perhaps more so than that of the well-known Amistead.

[Prince William, Virginia; Annapolis, Maryland Gazette, November 28, December 1, 1768; Virginia Gazette August 4, 1768; February 9, 1769; Pennsylvania Gazette December 15, 1768; January 13, 1769; February 2 & 9, 1769; LaBrew BMCP]

Billy “Fiddler” (1773)

Violin; essayed a second escape from William Fearson of Williamsburg, Virginia, November 4, 1773; he is the violinist described as belonging to the estate of Edward Nicholson; Fearson’s early announcement regarding hiring a violinist (November 14, 1769) resulted in Billy’s procurement.

[Virginia Gazette November 4, 1773; Ballou 8; LaBrew BMCP]

Billy (1759/61)

Violinist who ran away from Catesby Jones in Westmoreland county, Virginia August 26, 1779; was about 20 when he made his escape; he stood 5’, stout made, remarkably bow legg’d, lisps a little and looks very sullen when accused of any thing; “plays well on the fiddle;” brought up in the capacity of a house servant from his childhood; carried with him a new fiddle; $100 reward plus expenses offered for his capture; obviously captured and returned to his master; eight years later Jones advertised for Billy escaped again some eight years later on November 5, 1787; he was now about 5’ 4” or 5” tall and about 26 years of age; feet large, spoke fluently, thick lips and very white even teeth; escaped with JACOB; still played very well on the fiddle which he took; 5 Pounds if found out of state.

[Baltimore Maryland Journal and Baltimore Advertiser, October 5, 1779; November 23, 1787; LaBrew BMCP]

Binga, Arthur (1863)

Born in London(?), Canada; noted as a teacher at 508 Hasting street, Detroit, Michigan; mentioned in 1894 city directory of Port Huron (1894).

Census Detroit 1900 ED 49/10; Arthur, b. July, 1863, Canada of Canadian-born parents) barber; naturalized 1866; Ellen (b. March 1867, Canada of Canadian-born parents); Norman (B. April, 1895, Michigan); Arthur (b. 1897, Michigan); Raymond (b. Nov. 1900, 6/12, Michigan); LaBrew AAML (1987)

Binga, Victoria (18??-)

Performs as a vocalist with the “Colored Amateur Dramatic Association” at Eolah Hall and Jackson Hall in Saginaw City, Michigan; at Jackson Hall she performed “Topsy” in Uncle Tom’s Cabin in 1872.

[Saginaw Daily Chronicle February 15, 1872]

Bingley Field Band (1875)

Of Vicksburg, Mississippi.

[Vicksburg Daily Chronicle and Herald, April 22, 1875]

Binns, Charles (17??)

[Leesburg, Virginia; Washington Intelligencer, September 21, 1810]

Birch, Mme. Matilda (b. 1880-)

Soprano (born in Virginia) from Providence, R.I. with West Concert Company touring Kingston, Jamaica; see in Kingston Guardian; state and local officials present; wife of John Birch (b. May, 1877, Massachusetts) who is a member of Excelsior Band of Providence, R.I.

[New York Age, May 13, 1909]

Bird, Carrie (1875)

Music teacher born October 1875 in Philadelphia; father John T. (August 1845, Virginia), mother Labinda (August 1850, North Carolina); brother Robert (August 1874); 5 out of 6 children alive.

Census Philadelphia 1900 ED 132 5A

Bird, Joseph (1883-)

Musician.

Census Philadelphia 1910

Bird, William (1869-)

Musician born in Georgia of Georgia-born parents.

Census Buffalo New York 1900 ED 13/1B, b. Aug, 1869, 30

Birmingham Brass Band (Alabama) (1881)

“The brass band (colored) was on the streets Monday, from early morn to dewey eve, tooting for all they were worth, regardless of time of what anybody thought about it.” Negro dance house on 2nd Avenue “made enough fuss, day and night, to deafen the police force, and it did it, too.”

[Weekly Iron Age , December 29, 1881]

Birmingham, George Winthrop Maitland (1887/88-)

The strange tale told by a citizen of Barbadoes, George Winthrop Maitland Birmingham might well be more truth than fiction. It was first mentioned in the Detroit press.[14] But generally overlooked it details the travails of a young man whose mixed heritage crashed around him forcing not only his exile from his country of birth but also separated him from his family who were intent upon denying their black heritage which still remains in scholastic obscurity.

Negro Blood Makes Birmingham An Exile. As Wanderer Resembles His Mother, a Barbadoes Native. He is Paid to Keep Away from His Family.

Literally the black sheep of his family is George Winthrop Maitland Birmingham, aged 24, musician, stenographer, boot-black and remittance man of Barbadoes, England, Canada and the world, according to his story told at the immigration office yesterday afternoon.

Birmingham claimed to be a native of Barbadoes Islands, his father being an English colonist and his mother a full-blooded Barbadoes negro. Out of the family of children only himself and one brother, now an organist in Wales, show their African parentage. That is why he is a “remittance man,” paid an allowance as long as he stays away from his relatives.

“My father took us to England when I was 4 years old,” said Birmingham, after he had registered all his names at the immigration office. “I have a brother there now who has an important position in a bank, and two of my sisters are white and handsome girls. Another brother is on a ranch in Texas, and he sent me $125 to stay away from him, so as not to reveal his negro blood.

“I got a musical education, and was sent to Oxford, but I got into trouble through being one of the students who ducked ‘Prophet” Dowie on his visit to England. They fined us five pounds apiece, and my brother, who was afraid his name would get mixed into the affair as my brother, told me to get out of the country. I offered to go to South Africa on a hospital ship, but he insisted on my going to Winnipeg, Manitoba, brought my transportation, gave me a check payable only there, and sent a female detective to watch me until the boat sailed.

“I ran out of funds and worked as a boot-black in a hotel. Then I came here.

“I was engaged to a white girl, as pretty as an actress, and her family may have had something to do with sending me away.”

“Munchausen-like as Birmingham’s tale sounded, he was able to substantiate part of it. His lips are thin, showing a strain of Caucasian descent, and he talked with an english accent. He was tested on shorthand and on music, and showed himself familiar with both. He claimed to have worked as stenographer on the Michigan Informer [Detroit Informer?], an Afro-American publication. Getting out of work, he applied to the poor authorities, but was referred to the immigration office on account of his short residence. His case will be investigated.

Indeed, his name appears in the 1906 city directory and is further traced in the census of 1910. Also noted is his immigration date of 1904. In the draft registration of 1919 his birth is given as December 8, 1888 and is an “alien” born in the Barbadoes, West Indies. It is still possible to still trace him earlier in the 1891 census records of Great Britain in the Parish records of St. John, London. In that census the three brothers and two sisters are mentioned as residing with their aunt, Mary H. Bayley, age 47.

What we do not know, however, is whether he ever used his musical skill while in Detroit.

Birmingham, Henry G. (1868-)

Brother of George. In 1891 English census the word “musician” is crossed out. However, it is an indication that he possibly was a musician working in Wales at the time his brother George made this declaration.

Featured in Isham’s Octoroons; operatic singer; appeared in Detroit in October, 1893; also in Salsbury’s Black America (1895); reputedly from New York City.

[Detroit Sun October 1, 1893, p. 7]

Bivins, Lewis (1880)

Musician born January 1880 Pennsylvania; son of Lewis J. (July 1850, Virginia of Virginia born parents) and Sarah (October 1859, Virginia of Virginia born parents); brothers are Eugene (March 1886), Leon (August 1886).

Census Philadelphia 1900 ED 133 10b

Bivins, Nathan (1900fl.-)

Composer; started his own publish company ca. 1905; cannot tell if he is the same Nathan Bivins, age 57 (b. 1863 in Maryland) who in 1920 is listed as a patient in the Matteavan State Hospital, Dutchess County, city of Beacon, New York; in 1899 it was reported that he was using old melodies and passing them off as new and original.

Works

1898 Deed You Haven’t Treated Me Right, Hun, a coon climax song (M. D. Swisher)

1898 Gimme ma money, sg. (Geo. Willig & Co.); ded. to Williams and Walker; vln. & pfte. 1899

1898 The high toned colored ball, sg. (Geo. Willig & Co.)

1898 You cuts no figure with me, sg. (Jos. W. Stern & Co.); ded. to Hen Wise

1899 I ain’t seen no messenger boy, sg. (Hugh V. Schlam), full orch. arr. T. Jarechi & R. B. Poole

1899 I can’t see my money go dat-a-way, sg. (Jas. Hanrahan; ded. Billy McGuire

1899 I’Aint Seen No Messenger Boy

1899 I’se picking my company now, sg. (T. B. Harms & Co.); repro. Musical Supplement to N. Y.

Sunday Press, Nov. 11, 1900

1899 If You Don’t Like the Way I’m Doing, Pay Me Off, song (Witmark & Sons)

1899 This rag-time walk won the prize (Hugh V. Schlam)

1899 You got to do the Alabama Pas, Ma, La, sg. (T. B. Harms & Co.)

1900 Deed I’m Done With You (Witmark)

1900 Good-bye ma honey, if you call that gone, sg. (C. F. Briegel)

1900 Its Too Late to Be Sorry Now, song (Arthur W. Tams)

1900 Warm baby from the South, sg. (Hylands, Spencer & Yeager)

1900 You can’t fool me no more, sg. (Shapiro, Bernstein & Von Tilzer)

1901 I Don’t ‘Low No One to Throw Me Down, song (Willis Woodward Co.)

1901 I Want Some One to Care For Me (or Rosy Lee) (Willis Woodward)

1901 If I Don’t Change My Mind, song (Hugh V. Schlam)

1901 Take Me When You Go, song (Willis Woodward Co.)

1901 Tell me baby do, or whose lil’ babe is you (Dave Fitzgibbon, Butler & Co.)

1902 Ain’t That Gal a Dream, song, (McKinley Music Co.)

1902 You Can’t Join This Show,song (Howley, Haviland Dresser)

1902 You were never introduced to me, sg. (Howley, Haviland & Co.); sung Anna Driver with Tide of

Life. Co.

1903 She Certainly Looks Good to Me, song (Howley, Haviland Dresser)

1904 It Makes No Difference What You Do, Get the Money, An African argument (Feist)

1904 Miss Hannah Lee, song (Dowling-Sutton Pub. Co.)

1905 Don’t Worry About Any One Just Look Out for Yourself, song. (Nathan Bivens Music Pub. Co.)

1907 Down in Georgia on camp meeting day, sg.; wd. John Madison Reed; arr. with small orch.; arr. T.

Jareche, ms. (n.i.)

1907 If You Don’t Change Your Living, That’s the Way You’ll Die NBPC, American Music 15, p. 16, 1907; band/orch arr. J. W.Chattaway

1907 Linder Green (Nathan Bivens Pub.Co., American Music 15, p. 16, 1907)

1907 Love Me All the Time (Lemonier) Nathan Bivens Pub. Co., American Music 15, p. 16, 1907

1907 On The Board Walk After Nine (Jack Kenefick, arr. J. W. Chattaway) NBPC, American Music 15,

p. 16, 1907

1907 Pickaninny, it’s time you were in bed, sg. (Nathan Bivens Music Pub. Co.); wds. William McCall &

Bert Baker

1907 Pickanny, It’s Time You Were In Bed, wds. William McCall and Bert Baker American Music 15, p.

16, 1907

1907 Think of Me When I’m Gone (William Elliot) (Nathan Bivens Music Pub. Co.), American Music 15,

p. 16, 1907

1929 Don’t Tell Me I Don’t Know My Anna Lize, song (Louis Hass)

Census New York 1920, Dutchess County, city of Beacon, New York, ED 8 Sheet 5, line 45; who is Fred Bivins with George Jackson in Berlin, Germany? (Indianapolis Freeman, June 3, 1899)

Bizot, Celestine (fl. 1814/15)

Drummer born San Domingo in War of 1814 New Orleans, regt. of Fortier; Bizot is listed in Deville’s accounts with the D’Aquin Battalion.

Black, Billy [William] (fl. 1880s–90s-)

Works:

Every One Dem Chickens is Mine

[Indianapolis Freeman September 16, 1899]

Black Cesar (1700s)

Drummer in the Revolutionary War.

[National Archives]

Black Drummer (1700s)

Drummer in the Revolutionary War.

[National Archives]

Black, Elisabeth M. (1875-)

Actress, only daughter of O. H. Black (February 1843, Maryland, caterer) and Elisabeth (June 1859, Pennsylvania, barber) married 5 years and born January 1875 in Maryland.

Census Philadelphia 1900 ED 130 Sheet 5B

[1] Douglass Monthly, April, 1860, p. 252 mentions his performance in New Orleans.

[2] The account in the Christian Recorder, June 26, 1861 is taken from Dwight’s Journal, xxx xxx, xxx, xxx, xxx.

[3] He was due to arrive back in America August 19, 1865 aboard the City of Paris steamship.

[4] Free At Last by Arthur R. LaBrew (Detroit, Michigan 1976), mentions most of the important court cases involving Tom and General Bethune in addition to giving testimony from various music teachers and others that Tom was not the idiot that some modern writers attempt to portray. Tom’s abilities were genuine expressions that were rationally thought out. His ability in retentive powers was considered amazing!

[5] New York Times, Friday, Septemer 23, 1887.

[6] New York Dramatic Mirror, January 6, 1894.

[7] Indianapolis Freeman, August 3, 1895.

[8] Philadelphia Tribune, April 27, 1912.

[9] The 1865 publication by S. Brainard’s Sons (Cleveland) was entered into copyright by Root & Cady in the District Court of Illinois, plate number 710.

[10] Beginning with errors in the first paragraph she mispells Poznanski [“Pozananski”], fails to note the 1881 edition of Tom’s “Specimens of Blind Tom’s Vocal Compositions; incorrect name François “Sexaline” [Sexalise]; fails to list Songs, Sketch of the Life of Blind Tom=The Marvelous Musical Prodigy, etc. Baltimore: the Sun Book and Job Printing Establishment, Sun Iron Building; made his first public appearance in 1855 [not 1857]; was not compared “favorably” with Gottschalk as a pianist [Sears] but as a money maker; music not copyrighted under Bethune’s name (see above); programs did not “inspire” Blind Boone who refused to be classified with this “idiot;” Tom’s mental state was not that of an “idiot savant;” [This point was fully illustrated in an article Brainards Musical World, text in Free At Last, p. 55, 56 and further illuminated in “Additional Notes on Blind Tom and His Music” in AAMR 1/1 (July-December, 1981) pp. 104-130]; erroneously dates the Blind Tom’s March & Waltz 1851, 1854 respectfully which would have made him 2 and 4 years old! However, Ms Sears may not be entirely to blame because the editor, Sam Floyd and his staff, prepared all of the music entries. But, on the other hand, Ms. Sears must be faulted for allowing her name to appear in this article which she was asked to verify and submit substantial changes. The Black Music Center’s position that it was the sole authority on such matters was also exhibited in the article on Francis Johnson in which the first writer, Arthur LaBrew, refused to validate the music list prepared by the staff of the Center unless the music entries had positive cerification. So much for Boo-boos–Blunders & Bad Black Scholarship [title of a new work in progress.]. See also Berliner Recordings of Brilliant Quartet (1894, 1896) titled “Blind Tom.” [Check LC files for Berliner discography].

[11] National Anti-Slavery Standard, August 8, 1844.

[12] No Anti-Slavery song book by Bibb has yet been rediscovered. However, he published a “Collection of Songs For The Times,” in Slave Insurrection in Southamton County, Va. headed by Nat Turner, with an interesting letter from a fugitive slave to his old master: also a Collection of Songs for the Times, compiled and published by Henry Bibb (New York: Weseyan Book Room 5 Spruce Street, 1850). Copy in possession of the MMRC.

[13] This body of songs have seemingly gone unnoticed in writings about “slave” songs.

[14] Detroit Free Press, January 21, 1906.

Recent Comments