The Gulag Archipelago 50 Years Later– Reassessing One of the Greatest Works of Literary Realism

“Bless you prison, bless you for being in my life. For there, lying upon the rotting prison straw, I came to realize that the object of life is not prosperity as we are made to believe, but the maturity of the human soul.”

~Aleksandr Solzhenitsyn, The Gulag Archipelago

Background on Alexander Solzhenitsyn and his account of the Gulag

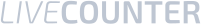

Alexander Solzhenitsyn (1918-2008) was one of the most notable Russian authors of the 20th century, having written perhaps the greatest nonfiction book of his time. His magnum opus, The Gulag Archipelago (1973) is a riveting chronicle of Solzhenitsyn’s enduring punishment by Soviet Communism in the harshest prison system on the planet. It contains records of 227 other individuals who suffered in the Gulag and provides interviews, reports, letters and memoirs that vividly describe the horrors endured by prisoners. Most prisoners, including Solzhenitsyn were branded as enemies of the state, with many having been former Soviet government officials or military. Solzhenitsyn was himself a decorated captain in the Soviet Army, detained in prison for his outspoken criticism of the evils of the Soviet Union and criticism of Stalin sent to friends via private letters.

Solzhenitsyn’s eight years in the Gulag was a transformative experience that enabled him to account for not only his own monumental sufferings behind bars, but revealed a rare record of 40 years of unjust Soviet terror and subjugation over Russia. Prior to the publication of The Gulag Archipelago, most citizens in Russia were content with Communist propaganda – blaming Stalin for the creating the horrible prison and various concentration camps to torture his political dissidents. However, Solzhenitsyn points out that it was Lenin, not Stalin, who created the Gulag, while the first concentration camps emerged during the 1920s under the Leninist government. Solzhenitsyn’s work also reveals that the great purge that saw the execution of many leaders of the Bolshevik Revolution was merely one of the many waves of mass death, with far more people having been killed by the end of the 1940s and into the early 1950s.

Solzhenitsyn would receive the Nobel Prize for Literature in 1970, a distinctive honor that he was unable to accept in-person due to the Soviet Union’s constant surveillance of his activities. Fearful of being captured or assassinated, Solzhenitsyn was forced to accept the award by a letter that was read at the ceremony in Sweden. Ironically, the event was hosted on International Human Rights Day, at a time when so many rights were trampled upon under the Gestapo boot of Communist tyranny and many prisoners in such regimes were dying from hunger.

Solzhenitsyn would be formerly expelled from Russia following the international publication of the Gulag Archipelago due to its direct condemnation of the corruption festering within the Soviet Union. This launched his fame and served to inspire widespread attention for the book, while its author was forced to reside in the United States until the collapse of the Soviet Union in 1991. Up to that time, no work had ever exposed the evils of the Soviet prison and concentration camps in such detailed, impactful, and comprehensive a manner as did Solzhenitsyn’s book. My article will provide analysis to the contents of this famous work, bringing its overall significance as a great work of nonfiction literature into focus exactly 50-years later. My analysis rests primarily on various quotations and references to the abridged version of the Gulag Archipelago, published by Harper Perennial Modern Classics (2007).

Analyzing passages from the Gulag Archipelago (abridged version)

In chapter 1, Part I, Solzhenitsyn begins his work by describing the wide variety of ways a targeted individual can be arrested by Soviet officials for transport to the Gulag. In every scenario, that person most likely will never be heard from again or will disappear for some indefinite number of years. The environment in Soviet Russia is one of continual fearfulness, with high expectations across households that any one person could be arrested and hoisted away by the state for any (or no) reason. Solzhenitsyn recalls his arrest being at the headquarters of his brigade commander, where he was surrounded by SMERSH (inspired by the phrase “death to spies”) officers. He knew his arrest was due to a correspondence he had with a school friend. Throughout chapter 3, Solzhenitsyn describes how Soviet prisons were either packed or overcrowded, but never empty or partially filled. Many of the prisoners were confined based on process crimes that were fabricated by the government. In order to force a “confession”, these people were tortured in their cells in a variety of ways. One method saw the extreme cooling and heating of the cell by the air-flow. The heat caused blood to ooze from the pores of some of the prisoners, and guards would only halt such tortures in order to haul the prisoners out for questioning. Intimidation was a widespread, effective tactic imposed on prisoners and those who were summoned by Soviet officials for direct questioning. Many prisoners were threatened to be sent to more brutal labor camps or harsher prisons if they refused to comply and answer questions.

Solzhenitsyn describes many of the excruciatingly uncomfortable or dreadfully painful methods of torture used by the Soviets to force confessions out of the imprisoned. Describing the prison management as idle, uncaring men with lots of time for devising torture tactics, they were capable of introducing a wide range of creative methods for harming their victims. Some of these included, depriving prisoners of sleep for days or even weeks, forcing them to stand in sub-zero water, beating a prisoner with a wooden paddle, continuously dripping water onto a prisoner’s forehead while they were strapped down, starvation, and trapping prisoners into unventilated and overheated rooms. In most cases, confessions were forced from prisoners, providing them with little to no legal protection. Some lucky few were offered a lawyer and/or were read portions of the national laws that they were found in violation of. Most were kept in the dark about what crimes they committed (usually fabricated) and were often kept in isolation during their arrest in order to heighten the feeling of hopelessness to the overbearing control of the state. The author describes the ideal state-of-mind that one should take in order to overcome the interrogator and avoid becoming trapped into making a confession:

“From the moment you go to prison you must put your cozy past firmly behind you. At the very threshold, you must say to yourself: ‘My life is over, a little early to be sure, but there’s nothing to be done about it. I shall never return to freedom. I am condemned to die—now or a little later. But later on, in truth, it will be even harder, and so the sooner the better. I no longer have any property whatsoever. For me those I love have died, and for them I have died. From today on, my body is useless and alien to me. Only my spirit and my conscience remain precious and important to me” (Solzhenitsyn, pg. 64).

By this, only the man who has renounced everything can win in interrogation. Solzhenitsyn regarded his first cell as the most memorable and symbolically important in a prisoner’s time at the gulag. With prisoners constantly being shifted from cell to cell, for stays that last minutes, while others lasted months, something about connecting with the people in one’s first cell resonated more than any other experience. The significance comes with the connecting with those in a similarly precarious predicament, surviving against all odds to endure the tortures of the Soviet state. Solzhenitsyn uses his brief chapter 9 to define how Soviet law advances in severity from the 1920’s onward, metaphorically associating this with the transition from boyhood to manhood. This transition began with the Five trials, including the 1922 Moscow and Leningrad trials against prominent Christian leaders, which led to the brutal execution of the defendants. The objective of the trials was to hastily advance the pillaging and subjugation of the Church by liberty of Lenin’s political section of the Criminal Code, containing an unlimited scope that targeted Russian Christians.

Part II describes how beyond the stationary prisons, prisoners were often transported by caravans, huddled together in containment on wheels. Soviets took every step to deliver prisoners without the regular townspeople in the area being aware, avoiding the controversy that would come with transporting masses of prisoners (nearly all of whom were innocent and abducted against their will) throughout populated communities. They sought to avoid risk in the loved ones of those abducted protesting or attacking the caravans. In chapter 2, Solzhenitsyn describes how the Soviets often choose to kill their targets in broad daylight when there are crowds gathered in order to make a political threat or statement to the masses. They choose not to kill certain targets at night because they hope to strike fear into the hearts of those who would consider revolting against the authoritarian regime in power. To this end, Solzhenitsyn issues a powerful lesson in Soviet fear-tactics: “But why like this? Couldn’t they have done it at night—quietly? But why do it quietly? In that case a bullet would be wasted. In the daytime crowd the bullet had an educational function. It, so to speak, struck down ten with one shot” (pg. 187).

The six lieutenants under Joseph Stalin are named and pictured toward the end of chapter 3. Headed by Genrickh Yagoda, they are Lazar Kogan, Matvei Berman, Yakov Rappoport, Naftaly Frenkel, and Sergei Zhuk. It is said that each of these three murderous men were responsible for the deaths of 30,000 individuals. And during times of war, wartime camps were more grueling, as less food and heat was provided to prisoners, while more work, severe punishment, worse clothing and brutal discipline was imposed. Prisoners who came as families or couples were split apart, and guards were constantly vigilant of abolishing any signs of love between male and female prisoners. There were said to be an upward of 10-15 million prisoners housed in the Archipelago, surviving in blizzard conditions throughout the Fall and Winter with few provisions. Solzhenitsyn describes how conditions were not often made any better for female prisoners vs. male prisoners. Females in many cases received grimier and more odorous prison cells without bedding. Those that were considered “attractive” were targeted by lustful male prisoners who fought with one another over rights to have the women as their own. All prisoners who were malnourished were at risk of getting scurvy, pellagra, or alimentary dystrophy, all terrible, debilitating diseases that the Soviet guards (for the most part) did not care to provide medical treatment.

In chapter 17, Solzhenitsyn mentions to his readers that no age group was insulated from the insatiable appetite of the Gulag, even kids. Article 12 of the Soviet Union’s Criminal Code of 1926 permitted juveniles as young as twelve years old to be sentenced to prison for assault, theft and murder among other crimes. They were only subjected to moderate sentences by comparison to adults. A startling statistic showed that in 1927, nearly half (48%) of all inmates at the Archipelago were youths aged sixteen—twenty-four (pg. 267).

Throughout part IV of the book, Solzhenitsyn describes how the Gulag was filled with many prisoners, particularly misguided youths, who mercilessly stole food from the weak and elderly. Instances where these individuals were robbed of their daily gruel and grits by gangs of youth are described in vivid detail. The singular law of the Gulag among prisoners was Darwinian in nature—survival of the fittest, as only “might makes right” in regard to who is allowed to eat and who isn’t. In chapter 1 of Part V, the concept of “katorga” is revealed as a term reintroduced by Stalin to be “murder camps”. According to the author, “in the Gulag tradition murder was protracted, so that the doomed would suffer longer and put a little work in before they died” (pg. 331). The camps saw prisoners work 12-hour work days with two shifts, with no rest days, allowing for an equal number of prisoners to always be working, while an equal number resided in the flimsy tents/huts they provided. Many were beaten to work harder and threatened by Tommy-guns at random.

In chapter 3 of Part V, Solzhenitsyn details that there was always a method to the cruelty of the Soviet torture imposed upon prisoners at labor camps. The many psychologists and designers of the camp structure were always thinking of new ways to maximize the torment and collective suffering of the prisoners under their occupation. The following passage describes this well in stating:

“How could screws already galling be made yet tighter? How could burdens already back-breaking be made yet heavier? How could the lives of Gulag’s denizens already far from easy, be made harder yet?” Transferred from Corrective Labor Camps to Special Camps, these animals must be aware at once of their strictness and harshness—but obviously someone must first devise a detailed program!” (pg. 346).

Solzhenitsyn undergoing a routine body search while imprisoned

For chapter 6 of Part V, Solzhenitsyn describes the harrowing efforts of a prison escapist by the name of Georgi Tenno, an Estonian orphan who served as naval and merchant sailor. Tenno was a tough, hardy prisoner who refused to give in to stringent interrogations by Soviet soldiers at the Gulag. He resisted many of their attempted tortures and deceptions, including ignoring the cries of a woman from a neighboring cell who the Soviets attempted to make sound like his screaming wife. Tenno was confined to the Gulag as a political prisoner from 1948 and was transferred between a series of Gulag labor camps, from several of which he facilitated or initiated a number of escapes with fellow prisoners. Tenno is defined throughout chapter 6-7 as the “committed escaper”, who developed a detailed 13-stage plan to escape from one of the prisons that included knocking out his interrogator with a severed bar from his metal bed frame, swapping clothes, hiding the body behind a desk, disabling the electricity in the interrogation room, and stuffing his cheeks to give the appearance that he is more fattened to mimic the interrogator. Although this particular plan never manifested, it enabled Tenno to have the high-powered confidence and strategizing needed to successfully launch other attempted escapes, one of which, saw him leave the confines of a labor camp. Though, he would later be recaptured and forced to serve the remainder of a 25-year sentence, where he died of cancer shortly afterwards.

Solzhenitsyn described the quintessential thoughts of Tenno, the committed escapist, during the night before launching one of his plans in the midst of the unforgiving Gulag prison: “The last night before escape! You can’t expect much sleep. You think and think…Shall I be alive this time tomorrow? Possibly not. And if I stay here in the camp? To die the lingering death of a goner by a cesspit?… No, you mustn’t even begin to accept the idea that you are a prisoner” (pg. 375). This line is key, because a large part of a successful prison break hinges on having a proper mindset as an escapist. The person must relinquish any false notions that he is truly a “prisoner” and allow his urgency to escape from this false imprisonment to drive his carefully planned, persistent efforts to hatch a plot to exit the labor camp undetected.

Overcoming the Gulag: Solzhenitsyn’s Legacy of Survival & Liberation 50 Years Later

With 2023 here, 50 years have passed since Aleksandr Solzhenitsyn’s classic work, Gulag Archipelago, was first introduced to the world. This brave and bold account of his survival in the hellish conditions produced by the Communist managed prison labor camps was ground-breaking. It marked the first and only time that anyone had survived a full sentence in the Gulag (in Solzhenitsyn’s case—8 years), which is a feat unto itself, while maintaining the mental strength and emotional courage to write about the pain and suffering he endured over the years there into a fully-published book. Solzhenitsyn also possessed the foresight and capacity to collect a host of accounts from his fellow prisoners who endured similar torturous conditions from the Soviets in power, serving to greatly enhance his compendium of stories outlined in the Gulag Archipelago. With so few resources and provisions available to prisoners, it is remarkable that Solzhenitsyn was able to compile these accounts to later produce such an organized portrayal of these sufferings in an authoritative, well-written, and compellingly vivid format. This work represented an experiment in literary investigation and was hailed by many critics, including Time magazine, to be the “best nonfiction book of the Twentieth Century”.

Solzhenitsyn’s work provides many timeless lessons on survival in the face of human suffering, perseverance through unfair imprisonments, and standing against an oppressive system of organized tyranny to overcome the maniacal controls of a Communist regime. Solzhenitsyn was resolute in the face of his interrogators, never yielding to their demands in a way that would compromise his integrity or manhood. While many of his accounts of how to survive in the Gulag seemed hopeless and inwardly depressing, he never urged his readers to abandon hope and often encouraged those who faced similar imprisonments to maintain attachment to their inner light that inspires one’s original hope (i.e., eternal faith in God, love of family, pride in one’s nation, etc.).

Solzhenitsyn’s work perhaps more than any teaches about the unique bonds that can be formed between prisoners who face similar sufferings and undergo shared experiences across the regular, punishment, and interrogation style cells. In fact, the first group of prisoners you meet during your initial arrival to the Gulag are those that impose the most powerful imprint on your memory, as Solzhenitsyn described a unique feeling of community that arises among those who coexist in their first prison cell. Solzhenitsyn’s work also teaches readers never to bow to the whims of the authoritarian state. If one is ever found to be in a similar situation where they are captured by a Communist regime for process crimes and are wrongfully imprisoned, Solzhenitsyn’s work teaches that such an individual must never allow the soulless authority of such a regime to crush their spirit. It teaches us readers to never become victimized by the horrors of imprisonment, but to endure its suffering to the bitter end.

The liberal mainstream media would have viewers manipulated into thinking that modern Russia, which threw off its former Soviet Communistic chains in the 1990’s, still maintains unmerciful prion systems that rival that of the labor camps portrayed in the Gulag Archipelago. They would give praise to the Biden Administration for “negotiating” a prisoner swap of lesbian WNBA player Britney Griner to be returned to the U.S. in exchange for the notorious Russian arms dealer and terrorist, Viktor Bout, and call this a “victory”. But, such are the falsities of the mainstream media, which overlook the fact that Russia has made many remarkable strides to alleviate its former Communist identity, transforming its economy, restructuring its government, and empowering its citizens to have representative authority in voting for members of the Federal Assembly.

Russia has also removed and reformed its abysmal prison system, as the Gulag was brought to an end on January 25th 1960, when the remains of the administration were dissolved by Nikita Khrushchev. The reality of the Griner-Bout swap was that Putin played Biden like a fiddle in allowing him to succumb to the cries among LGBTQ and social justice advocates to free Griner, while exchanging an individual who is known as the “Merchant of Death”, infamous for conspiring to kill Americans, funnel resources to terrorist groups, and export dangerous weaponry to authoritative regimes. This prisoner exchange was nothing short of a political failure for Biden and a strategic success for Putin.

In closing, Solzhenitsyn’s work must always be remembered as a victorious stance against the evil of tyrannical regimes governed by Socialism and Communism. Perhaps the greatest visual portrayal of his survival in the Gulag and insight into his stance against authoritarian regimes can be seen in his famous Harvard University Commencement address, (June 8, 1978) entitled “A World Split Apart”, which was what first led my father, Professor Ellis Washington, to greatly admire Solzhenitsyn as a prolific scholar and to model his literary output after his name sake’s (Ellisandro = Alexander) legendary example. Also, in the many essays my father wrote that mentioned Solzhenitsyn’s iconic literary output and his contributions to humanity, one essaythat in particular stands out titled—”Myths vs. Facts (Part 12) – Build up to the Civil War: The Political Terrorists”.

This address profoundly encapsulated the suffering that he underwent, while issuing a powerful realist message that exposed the evils of Socialism, Communism, and related political systems. This speech is a much see address that does well to accommodate his Gulag Archipelago and other celebrated scholarship. I end my essay encouraging readers to either examine Aleksandr Solzhenitsyn’s original three volume work or read the abridged version referenced in this piece. You will not regret your decision to do so, as the account of what Solzhenitsyn and others went through will transform your understanding of the Communist prison system (still prevalent in many countries) and the horrors of unchecked political subjugation by government fiat. I end with these important quotes from the Gulag Archipelago on the fine line between good vs. evil,

“If only it were so simple! If only there were evil people somewhere insidiously committing evil deeds, and it were necessary only to separate them from the rest of us and destroy them. But the line dividing good and evil cuts through the heart of every human being. And who is willing to destroy a piece of his own heart?”

“To do evil a human being must first of all believe that what he’s doing is good, or else that it’s a well-considered act in conformity with natural law. Fortunately, it is in the nature of the human being to seek a justification for his actions. ”

Category: Socrates Corner